The unseen and the in-between

Daniel Boyd with his artwork Treasure Island 2005, collection of James Makin, Melbourne © Daniel Boyd

Daniel Boyd has been the subject of much mythologising within the Australian art world. The softly spoken artist, a Kudjala, Ghungalu, Wangerriburra, Wakka Wakka, Gubbi Gubbi, Kuku Yalanji, Bundjalung and Yuggera man with ni-Vanuatu heritage, burst onto the Australian art scene in 2005 when he began to appropriate portraits of colonial explorers and members of the British monarchy, re-imagining them as thieving buccaneers. Here was a young First Nations man, exposing the perspectives and experiences of his people through histories long forgotten and purposefully erased. Therein lies the genius of Daniel Boyd.

Born in Gimuy / Cairns in 1982, Boyd – the youngest of three siblings – took to drawing as a child, often copying pictures that he found in comics and old books from around his home. For pocket money, Boyd made small paintings of the Gimuy reef, which he sold to locals and tourists. His artistic talents caught the attention of his family, who encouraged him to apply to art school following his completion of Year 12. Boyd, however, cheekily recalls that it was the slow realisation that he would not have a future in elite-level basketball that had him turn to a career in painting. At the age of 18, he exhibited work in A Place Far Away 2001, a group exhibition in Sydney, which in part assisted him in securing support for the presentation of his portfolio and subsequent enrolment in university study.

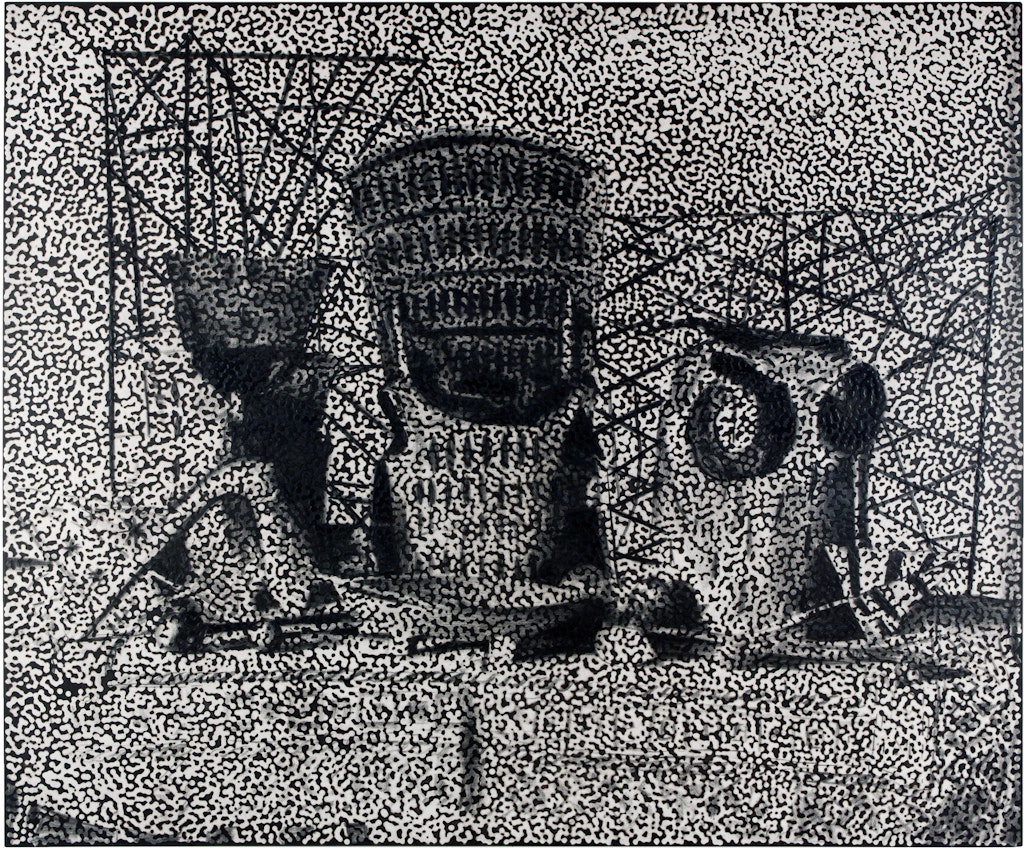

In 2002 Boyd began a bachelor of visual arts at the Australian National University’s School of Art & Design, Kamberri / Canberra. In 2005, his final year, he exhibited his now acclaimed body of work – the No Beard series – which successfully launched his professional career. Polly Don’t Want No Cracker Neither, his first solo exhibition, also in 2005, was held at Mori Gallery in Sydney and was roundly well received. So well, in fact, that the National Gallery of Australia purchased the entire show, including the painting Treasure Island 2005 – a coup for the emerging artist.

Daniel Boyd Untitled (TI4) 2015, collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne © Daniel Boyd, image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Daniel Boyd Untitled (TI4) 2015, collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne © Daniel Boyd, image courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

It seems only fitting then, that ‘Treasure Island’ should return as the title chosen by the artist for his first major monographic exhibition in an Australian state institution – Daniel Boyd: Treasure Island, which opens at the Art Gallery of New South Wales on 4 June 2022. An overt wink to Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 adventure novel of the same name, the phrase ‘Treasure Island’ has come to signify the extractive and exploitative impetus of colonisation in Boyd’s work.

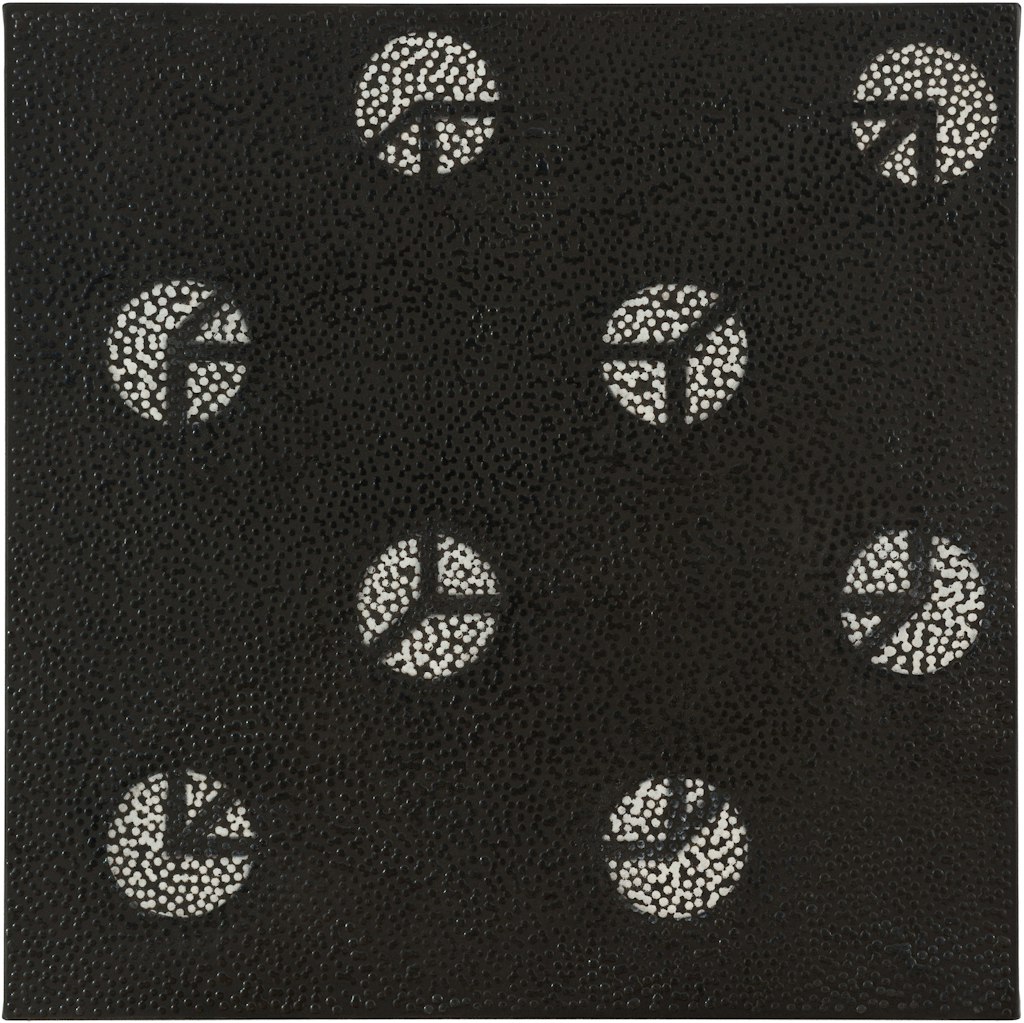

Stevenson has been immortalised in Boyd’s paintings several times since his early pirate parodies. In 2021, Boyd painted both a portrait of the writer, Untitled (FAEORIR), and Untitled (TIM) after a map drawn by Stevenson, which had been reproduced in a copy of the novel Treasure Island. Another work, Untitled (TI4) 2015, re-creates a photograph from an auction catalogue depicting artefacts that Stevenson collected in his later life while travelling across the Great Ocean and during his time living and writing in Sāmoa – among them, navigational stick charts, known as Rebbelib, from Ṃajeḷ / Marshall Islands. Stevenson is one of many metaphoric ciphers threaded through Boyd’s work. While ‘Treasure Island’ is, for Boyd, symbolic shorthand for the inherent immorality of colonisation, Boyd’s citation of Stevenson’s own collecting habits implicates him in the ongoing fetishisation of Great Ocean cultural material, which has fed western curiosity and artistic production for decades. As Boyd reminds us, the two cannot be disentangled.

As the pervasive presence of Stevenson illustrates, motifs and metaphors, images and ideas reappear again and again across Boyd’s near 20-year career. Never fully exhausted, subjects are woven like connective tissue through discrete bodies of work. When Boyd stages a show, its focal point is rarely narrow; the historical, the mythological and the familial are all intertwined. Narratives are reprised and early paintings are sometimes brought into dialogue with recent work. Attentive to the way in which Boyd navigates his own practice, the exhibition Daniel Boyd: Treasure Island is non-chronological. As a survey, it sprawls.

Both the exhibition and the book explore four different facets of Boyd’s work and together frame a study of the way he draws interconnected histories into close and vibrant proximity. The structure of the exhibition attends to his deeply nuanced inquiry into the complex and felt legacies of colonisation.

Daniel Boyd Untitled (WWDTCG) 2020, collection of Anthony Medich, Sydney © Daniel Boyd, photo: Luis Power, courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

Daniel Boyd Untitled (WWDTCG) 2020, collection of Anthony Medich, Sydney © Daniel Boyd, photo: Luis Power, courtesy the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney

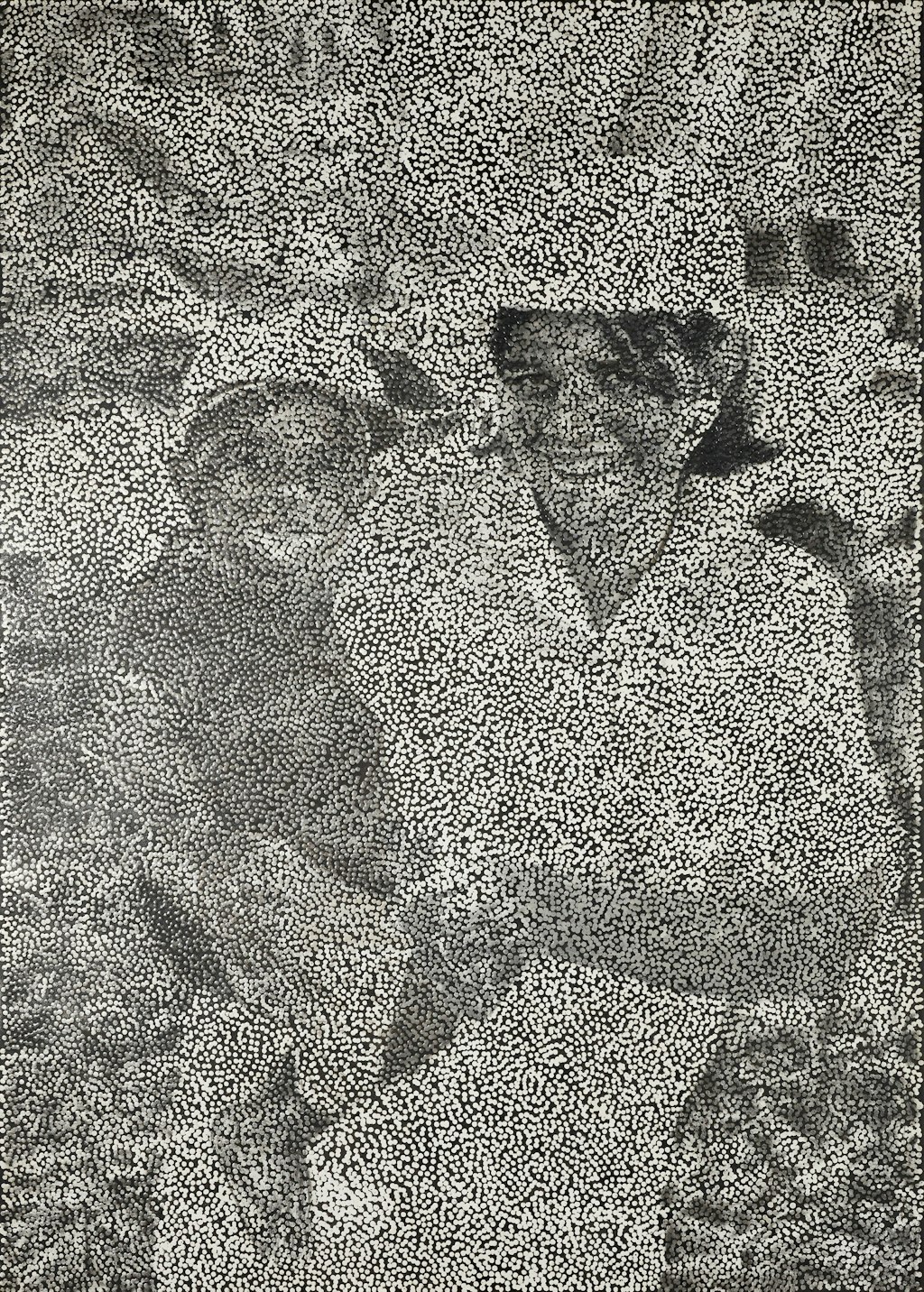

The first room introduces us to Boyd’s unique way of seeing the world. Since 2009, he has approached painting as an interlocked process of inscription and erasure. The clear, convex dots spread across his compositions hold and withhold information. They are islands of image fragments that bridge the black space that swallows the rest of the scene. An intervention into the act of seeing, these dots are referred to by the artist as ‘lenses’. For Boyd, his technique is informed by Gestalt theory, the allegory of Plato’s cave, and the search for dark matter, wherein the unseen and the in-between carry meaning. The works in this room, among them the mesmeric Untitled (SGN) 2016 and the captivating puzzle Untitled (WWDTCG) 2020, directly refer to these conceptual anchor points and contextualise the way in which Boyd upends our expectation of how a painting functions.

It is through an awareness of how Boyd reworks perceptive modes that we can see how he enlivens history – drawing out narratives that have been buried and all too often overlooked. This first room also features paintings of star maps and Rebbelib, devices that – like Boyd’s paintings – draw disparate people, objects and places together and connect fragmentary points across vast distances. That we encounter Boyd’s paintings of navigational devices here is intentional; these works orient us, equipping us with the tools to understand how Boyd re-images the past and draws attention to spaces in-between.

The second room reveals the abiding preoccupation of Boyd’s practice, placing his early No Beard paintings into dialogue with later work that extends his critical interrogation of colonisation. Re-figuring colonial paintings – whether by turning the protagonists into pirates or almost erasing them entirely – Boyd divests them of power. Where these paintings restage the ‘first act’ of colonisation as the loot and plunder of the pirates, the works in the third room address its ongoing legacies. It is here that Boyd’s rhizomatic logic unfolds and connections are mapped across histories.

First Nations slavery in Australia and the ‘blackbirding’ of South Sea Islanders (a term given to the indentured labour of workers in Queensland, taken from their homes by force or coercion) is enmeshed in the British sugarcane plantations in the Caribbean during the 18th and 19th centuries; in the White Australia policy enacted in 1901; and in the development of artistic modernism through the work of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. It is the indivisibility and entwinement of these stories that structures Boyd’s work. By making these connections explicit, he traces the networked violence that extends outwards from colonisation.

Daniel Boyd Untitled (ILYM) 2021, collection of the artist, Sydney © Daniel Boyd

Daniel Boyd Untitled (ILYM) 2021, collection of the artist, Sydney © Daniel Boyd

The final room considers the notion of legacy through a very different lens. Here, works that speak to cultural survival, inheritance and family lineage are brought together, and care and connectivity are foregrounded. Scenes appear from Boyd’s own life: his brother’s birthday party; a portrait of his grandmother; his partner against a landscape washed in vibrant purple. The tone is celebratory and tender. We are reminded that Boyd’s works are not divorced from the present, or from him. They are a witness and a chronicle; they are fragments within a practice that is as personal as it is political.

Boyd’s architectural and spatial interventions intersect with and speak to the ideas he explores through painting. His installations, including the 2022 site-specific works Untitled and Untitled (33.8688° S, 151.2174° E) commissioned for the exhibition, transport the lens from the surface of the canvas into a field of embodied relationality. Boyd has only just scratched the surface of what it means to take the lens beyond the canvas; to physically move the viewer through space via the articulation of a fragmented visual reality.

While it is made manifest in his architectural installations, all of Boyd’s artworks possess a speculative openness, inviting multiple entry and exit points. As a sympathetic gesture, the book accompanying the exhibition is designed to facilitate diverse encounters with his practice. The commissioned texts are written entirely by First Nations people. Essays by Daniel Browning, Dr Léuli Eshrāghi, Dr Michael Mossman and Nathan ‘mudyi’ Sentance offer critical insights into Boyd’s practice while poems by Jazz Money and Ellen van Neerven, as well as Boyd himself, provide experimental and emotive responses to the ideas explored in the exhibition.

Along with an in-conversation and photo essay compiled by the artist, these texts provide a matrix through which to understand Boyd and his work and offer a unique opportunity to champion Indigenous knowledges and ways of thinking more broadly. As curators, we have each contributed texts that delve into a specific aspect of Boyd’s practice: his fascination with and repurposing of objects, and his reanimation of historical photographs.

By no means an exhaustive overview of the artist’s practice to date, or of the deep thinking that fortifies it, Daniel Boyd: Treasure Island attests to the importance and critical resonance of his work within the current moment, where conversations around cultural survival, repatriation and the relevance of museums and archives continue to dominate Australian art discourse.

This is an edited extract from the publication Daniel Boyd: Treasure Island, available from the Gallery Shop.

A version also appeared in Look – the Gallery’s members magazine