Something always not seen

In the lead up to the opening of our new building, Justin Paton, the Art Gallery’s head of international art, descended into the Tank, a remarkable location from which to contemplate what art museums will be.

A light-drenched day in a sun-worshipping city. The harbour glitters expensively. It’s peak hour in the Sydney leisure-scape. Lunchtime joggers stampede past the Art Gallery. Down through the Royal Botanic Garden and Wahganmuggalee, where the Gadigal who have lived here for thousands of years gathered for ceremonies, cicadas chirr in the trees. Out at Yurong, where the joggers turn and pant back towards their offices, the view arranges itself obligingly: Bridge, Opera House, blue sea and sky, thrusting city …

Today, however, I’ve joined colleagues nearby to visit a lesser-known location. We’re on the outer edge of the Domain, just off the path down to Woolloomooloo from the Art Gallery, on a scruffy field whose sunburnt grass doesn’t see much lunchtime activity. This, we know, is the site where the Sydney Modern Project building will soon be rising: a new art museum on Gadigal Country. Yet our focus today is not the building to come but something already beneath us. After pulling on gumboots and receiving a safety briefing, we gather around a strange sight. A hatch has been opened in the surface of the world. We climb down out of the light.

This sounds like the stuff of fantasy – of fables, myths, science fiction. Think of all the stories of transformation in which the main characters descend, dropping below the ground-plane of the known to somewhere below and within. Think of Alice tumbling down the rabbit hole to a Wonderland where everything grows ‘curiouser and curiouser’, or the grieving Orpheus descending into the underworld ‘through the shadowy tribes and the ghosts of the buried’ to rescue his wife Eurydice. Think of the sun in Yolŋu tradition who travels through the earth at night to her camp, the warmth from her extinguished torch nourishing growth above.

Our descent into the Tank is, admittedly, less mythic. No payments to Charon – just a form to sign and those gumboots for protection in the disused space. But by the standards of an average workday, the experience is wondrously dislocating. The sudden drop from daylight to darkness makes it hard to see. What strikes us instead is atmosphere – a heavy coolness and stillness in the air. Columns march for what feels like miles in every direction, their forms doubled in the rainwater that’s pooled here. Sound travels weirdly as we descend the scaffold; the smallest ‘clink’ hangs in the air. Then, as we slosh our way to the walls, comes the revelation of time and texture: oil-stains, clay-streaks, time-scars. Though humanmade, this underland seems organic, even animate. Its richness makes the world above feel glary and insubstantial.

The empty Tank in 2018, with residual water reflecting the light from above ground

All of this happened in 2017 but the memory of the experience is strong. Architecture in its most predictable form announces its importance from afar. An ‘iconic’ building offers itself up as an image for rapid digestion and distribution. The Tank, by contrast, was thrilling to visit because there was no forewarning, no preamble. Climbing down, we entered a space we had hardly known was there, and which was, in its darkness and sensory intensity, impossible to capture photographically. We knew it would become a space for art – the fourth and lowest level of the museum that SANAA was designing. But because the space was pre-existing, it felt less like anyone’s ‘achievement’ than a common gift or a shared secret – ‘the treasure’, as SANAA architect Ryue Nishizawa called it on his own first visit in 2017.

As we know from fairytales and fables, treasures come with obligations. It is not enough just to receive or ‘discover’ the gift. The receiver must also recognise its value, and prove themselves deserving. Appreciating the stupendous atmospherics of the Tank is part of that recognition. But the encounter also demands that we reckon with what the Tank was. For the ‘treasure’ and its astonishing properties are products of a specific history, one that formed our present but which is, like the Tank, easy to overlook. To descend into the Tank is also to descend into a space of 20th-century conflict.

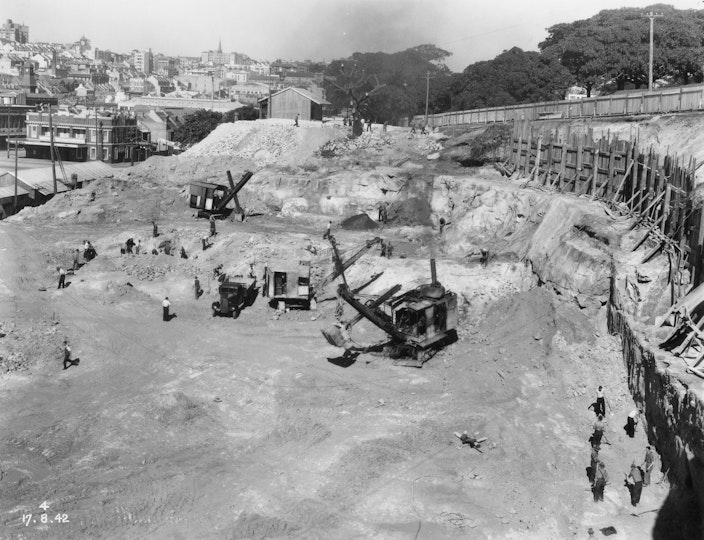

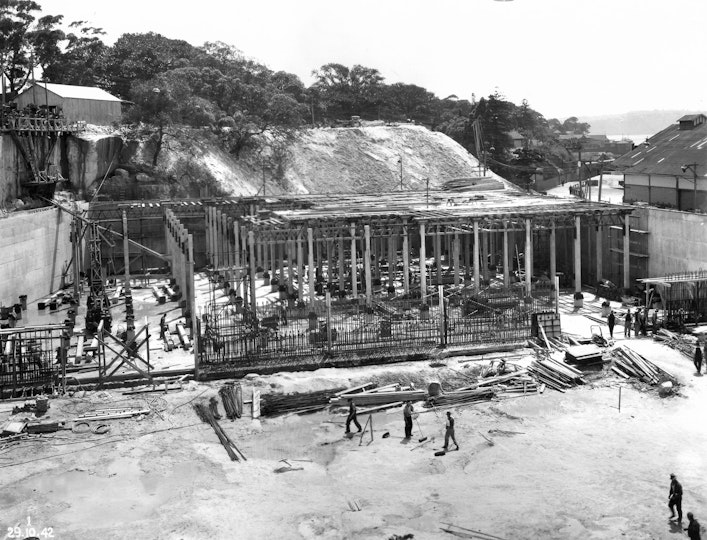

Plans to build the Tank in this location took shape in a flurry of secret government correspondence in May 1942. Following the fall of the British naval base in Singapore to Japanese forces earlier that year, an urgent need arose for sites to fuel and repair Allied war vessels in the Pacific. The scale and speed of the resulting build can be glimpsed in a notice in the Sydney Morning Herald on 11 July 1942, calling for the delivery of 2260 tons of cement and 10,000 cubic yards of gravel to the Domain within four days. By August of 1942 the site was swarming with labourers, working to create what was, effectively, a war machine: two connected bunkers holding around 19 million litres of oil that would be pumped to ships across the bay. With its mighty expanses of form-worked concrete and forest of more than 100 precast columns, the Tank belongs to a worldwide network of bunkers and defences created during the Second World War – an architecture of crisis that reached from the Nazi fortifications on France’s north-west coast to coastal gun emplacements in Aotearoa New Zealand. Constructed not long after submarines of the Imperial Japanese Army attacked Sydney Harbour and bombed Sydney and Mulubinba/Newcastle, the Tank, which was decommissioned in the 1980s and has lain unused since, is an unseen yet imposing reminder of Australia’s involvement in a new kind of war that was capable of reaching anywhere (the page of the Herald mentioned above features advertisements for ‘AIR-RAID SHELTERS, factory or home’).

Construction of the oil tanks in 1942

Construction of the oil tanks in 1942

Construction of the oil tanks in 1942

Aerial view in 1943 showing the Art Gallery and Woolloomooloo Bay, and the not-yet-turfed roof of the two oil tanks

It is not unexpected to see art now arriving in a space vacated by war and industry, but if there is one word that distils the Sydney Tank’s unique character, it is locatedness. Built into the curve of a quarried hillside, with sandstone at its back and ocean adjacent, the Tank is an aggressively human, wartime structure that feels powerfully dug in, embedded. The sense of architecture infiltrated by nature was acute on our first visit, when we marvelled at the slender stalactites of sand in one corner and the tree roots that had grown downward in another, their blind tips webbing out to soak up available moisture. Even now, with those ‘growths’ removed, the Tank’s material life is insistent. Salts and minerals bloom on the walls. Horizontal accretions mark tidelines. And every vertical surface in the space carries a petroleum patina.

This patina, more than anything else, discloses the Tank’s unusual history and paradoxical character. For the oil that was held here to fuel a war was itself an extracted product – a dark substance formed of the altered bodies of ancient organisms, drawn up through the earth. And the fossil fuel, having filled this container for decades, has impregnated its concrete interior, so that the Tank possesses, in low light, the leathery glow of a Rembrandtesque chamber. So, the accidental monument to war is also, now, an oil-stained memorial to the fossil-fuel era, while having additionally become an unlikely nursery for peculiar and persistent natural forms. Histories of human labour and extraction merge disorientingly with ‘biological’ incursions, leaving an onlooker wondering how, and even if, the natural and cultural can be separated.

The challenge for art in the Tank is to surface these contradictions rather than leaving them buried. How to recognise, without trying to resolve or reconcile, the turmoil of histories and existences in this location? And how, in the process, not to be overwhelmed by the presence of the Tank itself? Art is often enlisted to bring interest and texture to architecture that has been disinfected of context – the ubiquitous ‘white cube’ of the contemporary art-system. But the Tank is a found object so charged with history and irony that it scarcely needs art’s assistance. The art it does need will have to be ambitious but also, strangely, humble – more interested in channelling the power that is already there than in asserting its own unique presence.

Adrián Villar Rojas testing sound in the Tank in September 2018

All good stories of descent into the underworld involve a main character, and so it is in Sydney. Argentinian Adrián Villar Rojas is the first artist to present a project in the Tank – though the anodyne language of ‘presenting projects’ does no justice to what he is undertaking. Curious by temperament and committed to what he calls a ‘bodily investment’ in the places he works, Villar Rojas spent many hours, in the era before COVID-19, getting to know the Tank physically: absorbing its atmosphere, pacing it out, meeting acoustics experts in situ. He stared at the roots that grew down the walls. He swung torches to explore the movement of shadows. He ran sound from his phone through a mobile speaker and felt the whole space reverberating. He witnessed many fugitive effects of light and sound that will never be repeated.

But, as rich as these visits were, the most galvanising insights emerged above ground during discussions with staff, particularly archivists and Aboriginal curators and educators, about the history of the Art Gallery and its site. A self-described ‘housekeeper’ who has created assumption-testing projects at The Met in New York, MOCA in Los Angeles, and Kunsthaus Bregenz in Austria, Villar Rojas works always from the understanding that ‘the container is the content’ – that the institutional frame (its walls, its workings, its workers) is as charged and expressive, as capable of ‘meaning’, as the art within it. During conversations with the Art Gallery’s head archivist Steven Miller, Villar Rojas was especially struck by aerial views of the evolution of the Art Gallery ‘container’. From its neoclassical facade to its modernist 1972 extension to the addition and renovation of Asian and contemporary galleries, the museum unfolded down the hill like a surrealist exquisite corpse, an architectural collage expressing the Art Gallery’s evolving identity (and occasional identity crisis). Looking down at all this from above was, Villar Rojas said, like looking into someone’s brain.

The new building, as Villar Rojas observed, would update and reset that history, exchanging the imposing monumentality of Walter Liberty Vernon’s Greco-Roman facade for the lightness of SANAA’s slender columns and glazed facades. But the dialectical key to the expanded art museum was provided, unexpectedly, by the Tank.

The interior of the Tank, February 2018

The interior of the Tank, February 2018

If looking at the Art Gallery from above was like looking into someone’s brain, then descending to the Tank and walking among its forest of columns was like entering the museum’s architectural unconscious – a mirror space, an upside-down, that reflected the museum back at itself unexpectedly. Looking back up through the layers of the museum from the vantage provided by its war-era basement, one registers afresh the shocking recentness of Western art’s arrival in this place, and how that category has itself been churned and changed within larger movements of war, empire, exploitation, extraction, trade and labour.

Of course, the Tank will primarily be a space for the art called contemporary. As I write, it is being fitted with the services that will make it exhibition-ready: lighting tracks, floor boxes, service boards, air registers, data cables and so on. The space eventually encountered by visitors will surely earn those words so prized in the ‘experience economy’: spectacular, immersive, multisensory. But Villar Rojas’s provocations also make me hope that the Tank will be – a very different word – haunting, and that, in the process, it will test and unsettle the way we use the word contemporary. Today ‘contemporary art’ is a historical term, associated with the emergence of a market and a field of study and institutional attention in the 1960s and 1970s (the Art Gallery appointed its first curator of contemporary art in 1979). The defining expression of the contemporary in museum architecture is the impeccable white cube or art fair booth, a space that does not smell or sweat and which declares itself perpetually ready for the now and the next.

In every way, the Tank denies this dream of neutrality and nowness. Those marks on the wall – are they chemical or mineral? Natural seepage or recent intervention? The acoustics, geometry and even smell of the Tank amplify and accelerate that confusion. The space holds and uncannily prolongs any noise you make. The column grid creates, as you move, a constant flick-flack of lateral perspectives. The sheer size of the Tank, combined with its darkness, makes the space, though vast, feel elusive. It’s hard to photograph; it won’t be held in one view. Something is always not being seen.

Here lies the Tank’s potential as a space for what I’ll call constructive haunting. It is, as we’ve seen, a matchless space in which to be haunted by what has happened – to feel the layering of lives, thoughts, work and matter since its construction. But it is also – and this is where things get heady – a fitting place to be haunted by the future. For if there is one thing that distinguishes the art museums of now from those of, say, a century ago, it is a sense of their own precariousness and mortality. Museums, traditionally seen as safe houses for vulnerable objects, now strike us as vulnerable objects too – the improbable adornments of a civilisation that is rapidly consuming the world that sustains it. We are conscious not just of the futures we dream of but of the futures we have already lost – the future in which, say, the Great Barrier Reef is not dying, and Canada is not enduring freak heatwaves. The rhetoric of newer and better needs to be countered by a chastened sense of roads no longer able to be taken.

‘What kind of ancestors will we be?’ asks philosopher Roman Krznaric. With its uncanny echo, its connection to conflict, its scars of use and disuse, and its changing physical state, the Tank is a remarkable location from which to contemplate what art museums will be – what they will hold, how long they will last, what they’ll keep doing and what they’ll relinquish. Excitingly, these are philosophical questions that we’re now working through in practical ways. With Villar Rojas as a kind of spatial dramaturge, the Art Gallery’s conservators, curators, designers, installers, educators and front-of-house teams are, so to speak, down in the basement together with the artist discovering what kind of space it can be. The Tank is now characterised, in the words of head conservator Carolyn Murphy, as ‘a space alive’, a site whose specialness lies precisely in the fact that it is changing and will keep doing so. Preservation and control, the reflex responses of institutions accustomed to collecting precious objects, are being replaced by an ethos of active observation and ‘working with’, as the Tank’s new tenants learn to live in a space hat’s still breathing, seeping, drying, reverberating.

The interior of the Tank before its conversion into a gallery, with tree roots descending from the grounds above, February 2018

At present, for instance, the Art Gallery’s conservators are attending closely to the Tank walls and their rich confusion of industrial stains – the aim being to understand how Villar Rojas can create new markings that collaborate with ‘the walls as something active’. A related conversation has unfolded around the now-demolished northern Tank. On learning that this adjacent space was to be removed to make way for a loading dock, conservation lab and other facilities, Villar Rojas immediately asked if he could salvage some of its remnants. Columns, plinths and other offcuts now lie under tarpaulins at the Art Gallery’s offsite storage, ready to return to the southern Tank as part of Villar Rojas’s work. This act of recycling will also be an exceptionally visceral form of haunting – the ‘bones’ of the gone Tank cradled within the standing columns of its twin. What an image this is, of the art museum as a self-conscious, self-critical and sometimes self-consuming organism – feeding off its own losses and gains, swallowing and trying to digest its own history.

In the time between his last visit to Sydney in 2019 and his imminent return, Villar Rojas’s relationship with the Tank has deepened in remarkable ways. Prevented from visiting in 2020 and 2021 by the global pandemic, Villar Rojas and his collaborators found another way to be local, using gaming software to create a lovingly detailed version of the Tank that permits them to dwell in it fully – testing the fall of light, the swing of shadows, the roll of sound, the movement of people. From their distant yet connected spaces in New York, São Paulo and Villar Rojas’s hometown and studio base in Rosario, Argentina, he and his team began to occupy and populate the Tank’s mighty volume with what he calls ‘receptive forms’: sleepers, monsters, collisions, depositions, irruptions, grafts, broken marvels.

Then, as if mimicking the way the Tank itself has been altered by time during its years of disuse, they subjected those forms to a kind of temporal sculpting – sending them virtually to distant times and places to endure whatever awaits them, and then retrieving them to observe what remains. It is these forms – troubled, wondrous, non-Euclidean, incommensurable – that are now being made real in the large and bustling workshop Villar Rojas has established for this project in Rosario.

View from live environmental simulation generated by 'Time Engine' software © Adrián Villar Rojas, 2022

At Adrián Villar Rojas’s workshop in Rosario, Argentina, the sculptor and modeler Georgina Bürgi at work on a sculpture for The End of Imagination, photo: Mario Caporali

At Adrián Villar Rojas’s workshop in Rosario, Argentina, the sculptor and modeler Ariel Torti at work on a giant sculpture for The End of Imagination, photo: Mario Caporali

At Adrián Villar Rojas’s workshop in Rosario, Argentina, the sculptors and installers Matías Chianea, Alejandro Cinalli, Marcos Giovanini, Aurelio Cossar at work on a sculpture for The End of Imagination, photo: Mario Caporali

But I am, I fear, getting ahead of myself, and giving too much away. The final contours of Villar Rojas’s project are not fully known at the time of writing, and, even when they are, the unknown will remain an essential element – a quality, a pressure, that Villar Rojas will work with as physically as he does any of his real materials. In a world where experience is increasingly pre-named, observed, tracked, quantified and instrumentalised, our dream is to offer to visitors some version of the wondrous disorientation that overcame us on first visiting the Tank. And the deeper dream, as those visitors gain their bearings, is to make that disorientation productive – to open a space where anyone is free to contemplate what they had not seen, what they did not know, what they had never realised or anticipated. This freedom has value anywhere, but one could argue that it has special value in a new art museum on Gadigal Country, on a storied site whose Indigenous history precedes beaux-arts temples and wartime fuel-bunkers by millennia. Perhaps the most important moment will not be when we descend into the Tank but when we come back up from it, newly conscious of all there is to see and know in the ground beneath our feet.

A version of this essay appears in the book The Sydney Modern Project: transforming the Art Gallery of New South Wales, available from the Gallery Shop