Anna is a palindrome

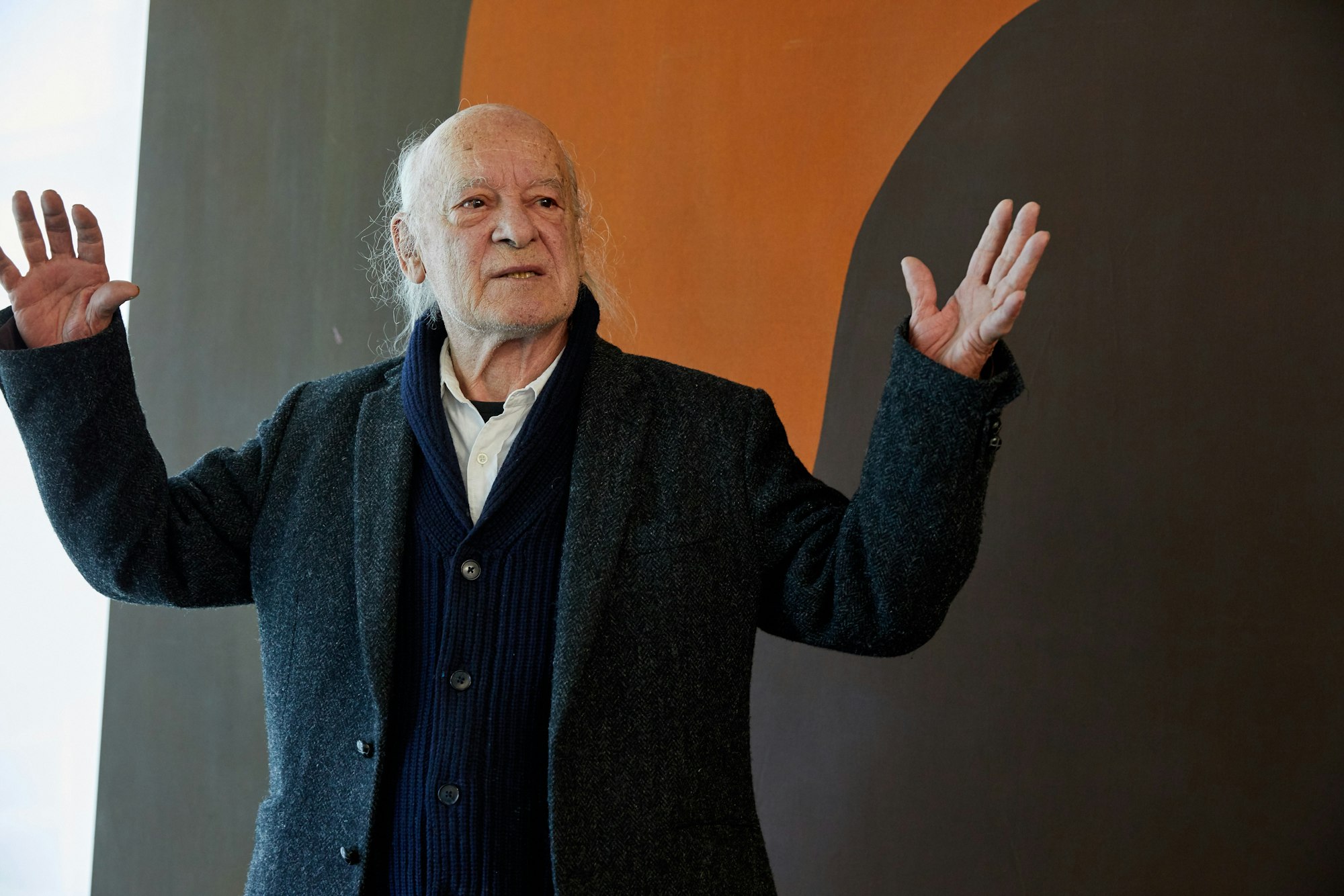

Michael Johnson with his 1965 painting Anna

Anna is a palindrome – a word or phrase that reads the same backwards as it does forwards.

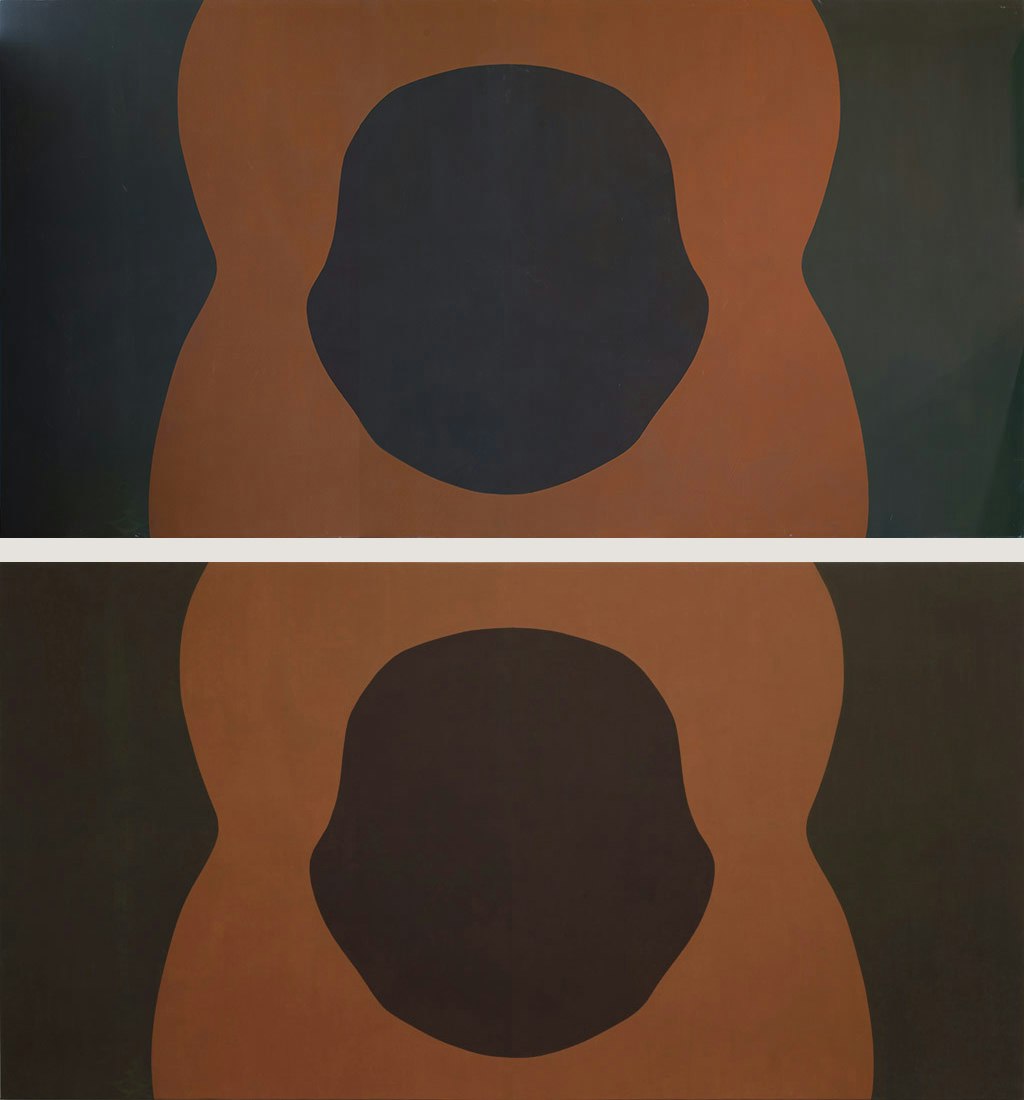

It’s also the title Australian artist Michael Johnson gave to one of his large-scale paintings and a smaller study in gouache that preceded it, both now in the Art Gallery of NSW collection.

For Johnson, works such as these are visual palindromes – abstracted, symmetrical forms that can be read the same way from any direction they’re viewed.

Johnson was a pioneer of colour field painting in Australia and one of a generation of expatriates who lived and worked in Europe or New York in the 1960s.

Created in 1965 when he was living in London, the painting Anna is based on a nude drawing he did of his wife Margo. It is one of his first paintings produced with polyvinyl acetate (PVA) paint and is representative of his aesthetic at the time, which presented geometrical shapes in even, flat and matt colours.

Originally titled Burnt Umber Raw Sienna Raw Umber, the painting was exhibited for the first time in 1965 in the second Commonwealth Biennial of Abstract Art exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute in London. The artist changed its title to Anna after the birth of his daughter and it is under this new title that it was exhibited at Sydney’s Central Street Gallery after his return to Australia in 1967.

The Art Gallery of NSW acquired Anna in 2018 thanks to the Patrick White Bequest Fund, which also funded the extensive conservation treatment needed before it could be displayed.

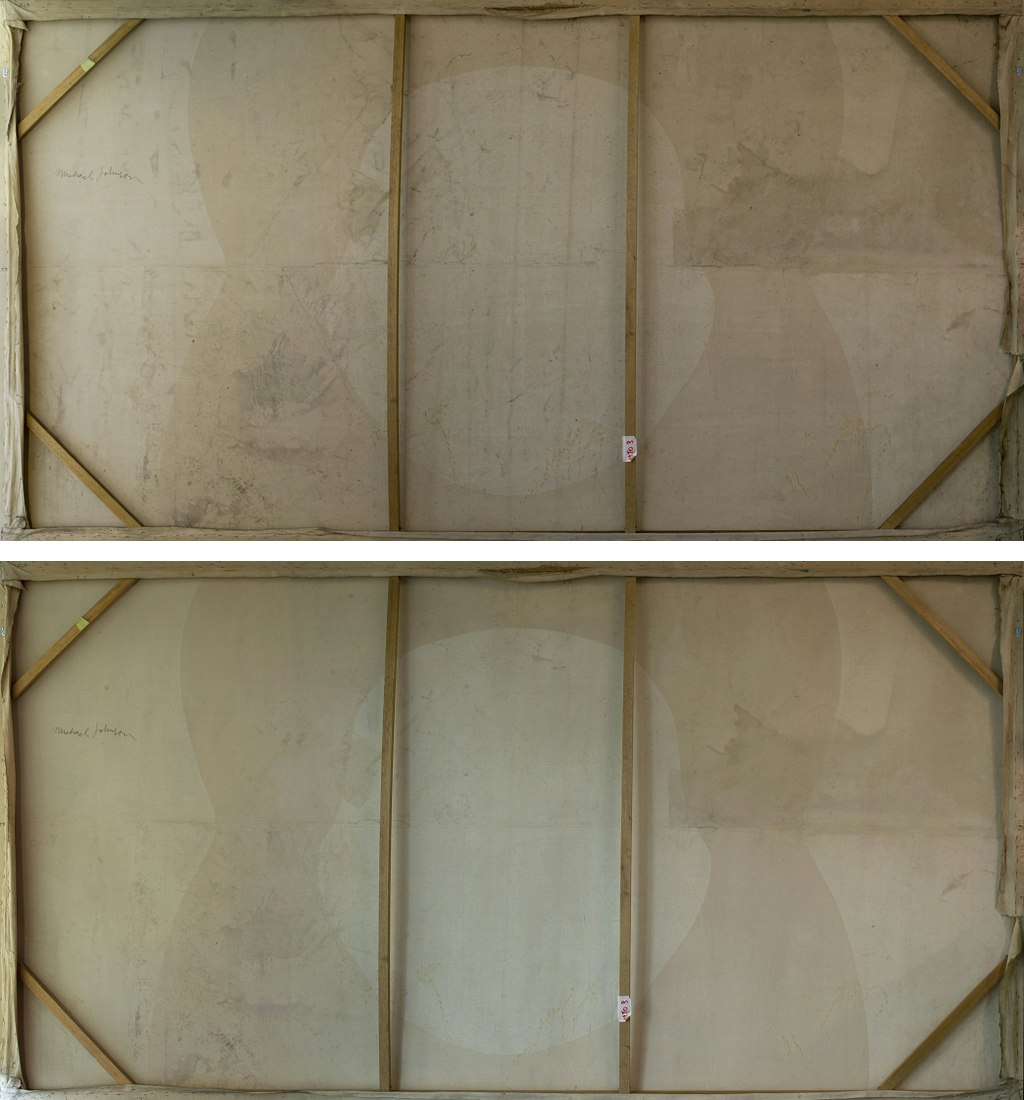

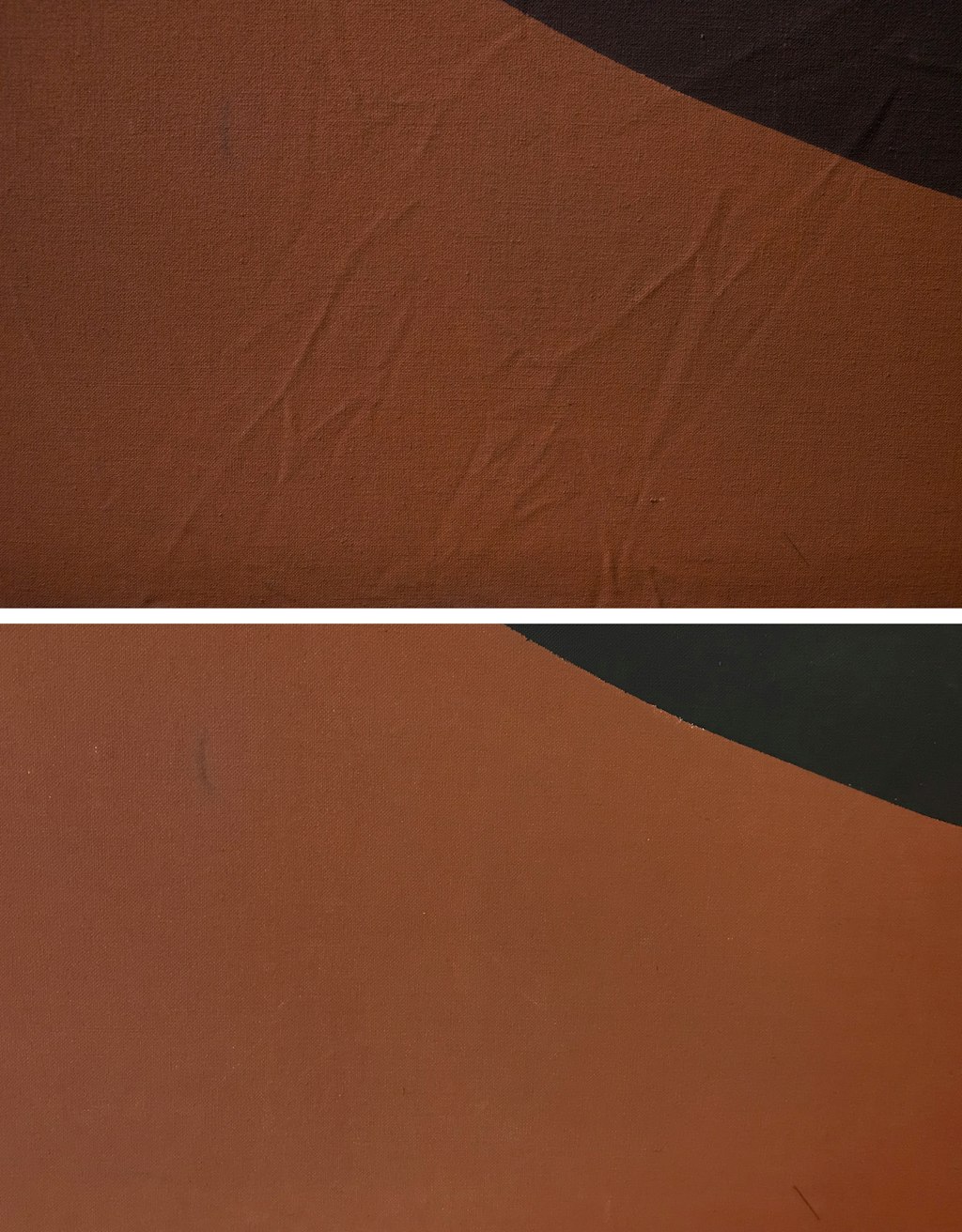

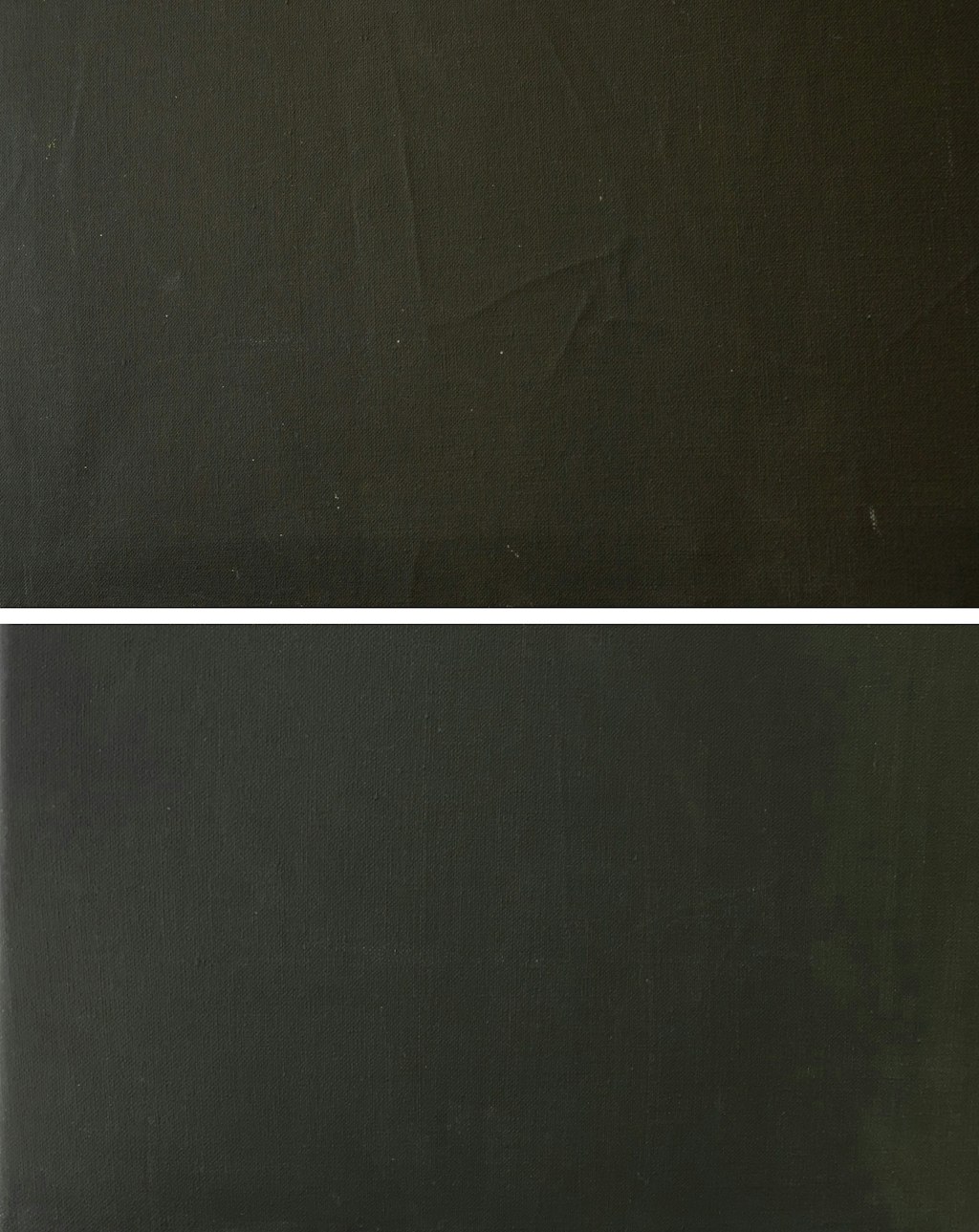

Michael Johnson's Anna before (top) and after (bottom) conservation treatment

The first step of this project was to closely examine the painting in order to identify and localise the damage on the canvas support, strainer and paint film. It was photo-documented before, during and after treatment and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis of samples of the three colours was undertaken to confirm the nature of the medium and pigments used by the artist.

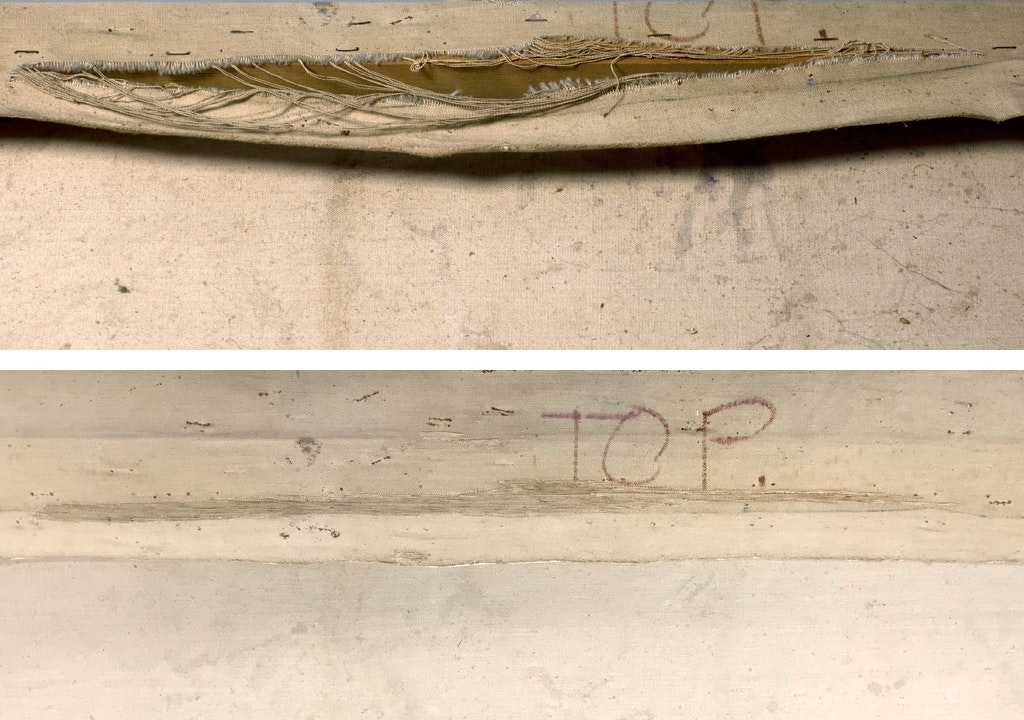

Several types of damage were noticed on the canvas. Many tears weakened its stability, two of which were on the front of the work and the others on the tacking edges. The tension of the canvas was very loose, creating a bulge along the lower edge.

Because of its large size (more than two metres by four metres), the canvas had been removed from its original strainer and rolled or folded to travel from London to Sydney in 1967. This created many creases in the canvas which were visible on the front of the work.

The surface of the painting was stained in many places and a thick layer of dust dulled the colours of the paint film, which was covered with numerous scuffs, scratches and abrasions. These types of marks are often found on fragile matt surfaces and were particularly visually disturbing as the evenness of the colours is essential to the painting’s aesthetic.

The conservation treatment started with a thorough dusting and dry surface cleaning of the front and back of the painting.

The wooden strainer wasn’t original so we decided to replace it with a new, stronger stretcher made from aluminium.

In preparation, the canvas was removed, which gave good access to its back and to the tears which could be treated first.

These were consolidated by joining their edges with a mix of natural glues then sailcloth patches were added to the bigger ones to strengthen them. Conservation intern Marjolein Hupkes assisted with this stage of the treatment.

Strips of sailcloth were also glued to the tacking edges to reinforce them for the re-stretching of the canvas onto the new stretcher.

Stretching such a big canvas requires quite a lot of strength to obtain tension across the canvas so assistant conservator Melissa Harvey and reproduction frame maker Tom Langlands helped with the process.

Strip lining attached to the back of the canvas

Re-tensioning the canvas flattened many small creases. The remaining ones were treated by placing the painting face down on tables and using localised moisture and pressure on each of them.

Once the stability and flatness of the support were re-established, the treatment of the paint film could be undertaken. The scuffs, scratches and abrasions were retouched using a mix of medium and dry pigments applied in fine dots to the damage itself, without covering the original paint. The difficulty in retouching such paint film is to obtain a finish as matt and even as the original while using a different type of medium. It is very important that the retouching remains distinguishable and reversible in case it needs to be removed in the future.

When the treatment was completed, Michael Johnson himself was invited to the Gallery’s conservation lab to meet with Denise Mimmocchi, our senior curator of Australian art; Paula Dredge, our head of painting conservation; and me.

Visits by artists are a welcome opportunity to ask questions regarding the history of the work and the materials used to create it. These conversations and hearing a first-hand account of their experiences making their work are one of the advantages and great pleasures of working on contemporary artworks.